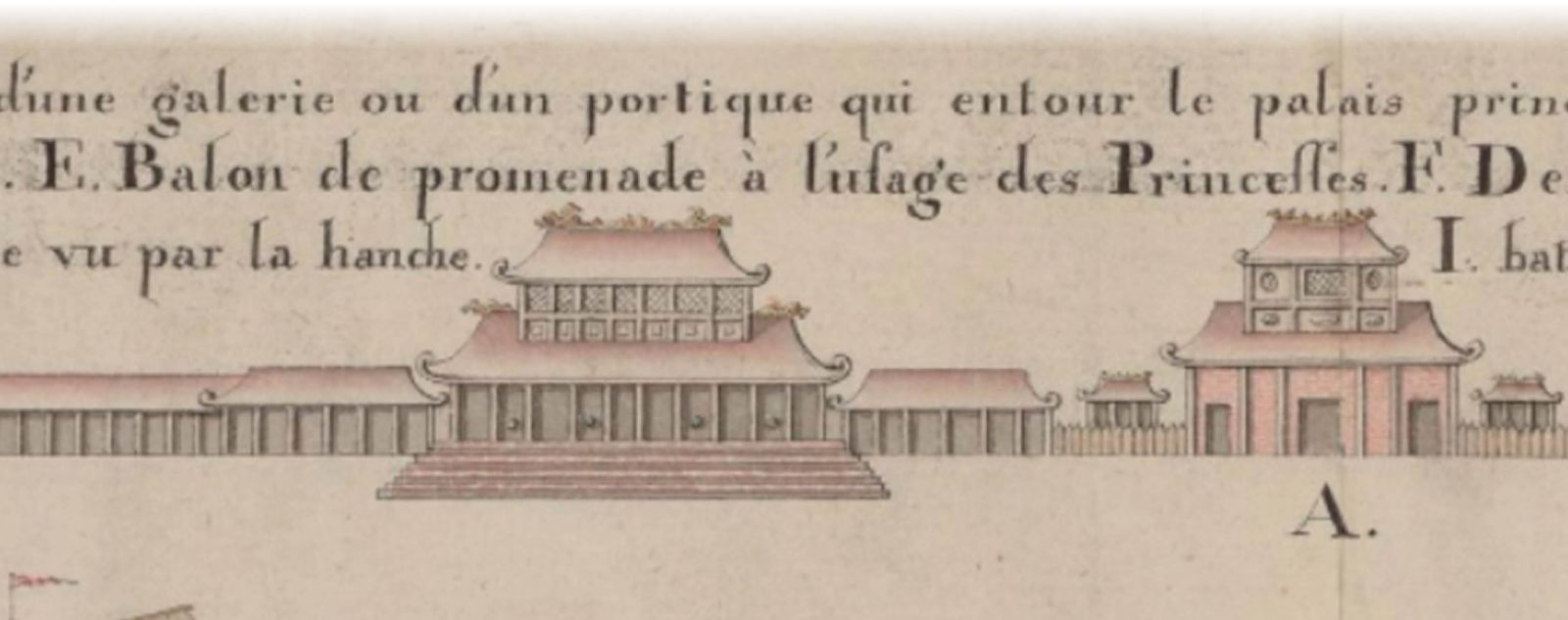

The gate of the Capital of Phu Xuan (Le Floch de la Carrière, 1755-1756)

With the aspiration to renovate, the Nguyen lords always welcomed foreign merchants and experts. Since the 18th century, many Jesuits had hold many important positions in the imperial court of Phu Xuan. In 1686, Hien Vuong (Virtuous Lord) even sent a letter to the House of Lords in Macao, asking to return the physician Bartholomeu da Costa. If not, he would claim to be the enemy of Macao.

In Vo Vuong (Martial Lord) Nguyen Phuc Khoat’s era, due to many changes, there remained the only physician Koffler. In his book A Historical Description of Nam Ha (South of the River) (Description historique de la Cochinchine, Revue Indochinoise, 1911, Vol. 15), he provided lots of interesting information about life and festivals including Tet Holidays in Hue.

Lunar New Year was the most important festival in Dang Trong. Preparation for this great festival lasted up to 20 days for the king and mandarins while 3 days for laymen. The ritual of setting up cay neu (neu pole) was considered especially important, not only in the imperial city but also in private homes.

People solemnly chose tall bamboos, with some bunches of green leaves on top. The strange thing was, they tied the leaves into bundles or included some pieces of old bamboo called cotton tubes (to make flower with bamboo thread?) Hue people also decorated cay neu with things like gold paper and silver paper, a handful of straw and a small basket in which they put some money as payment for happiness which they thought they bought from heaven in this formal ritual.

Since this ritual was considered very important, people must choose the day and time carefully for the erecting and lowering of cay neu, ensuring dispelling bad luck and bringing good luck. In case cay neu fell because of wind or any other causes, it would be the worst omen for a very bad year for the clan, the village and the whole kingdom.

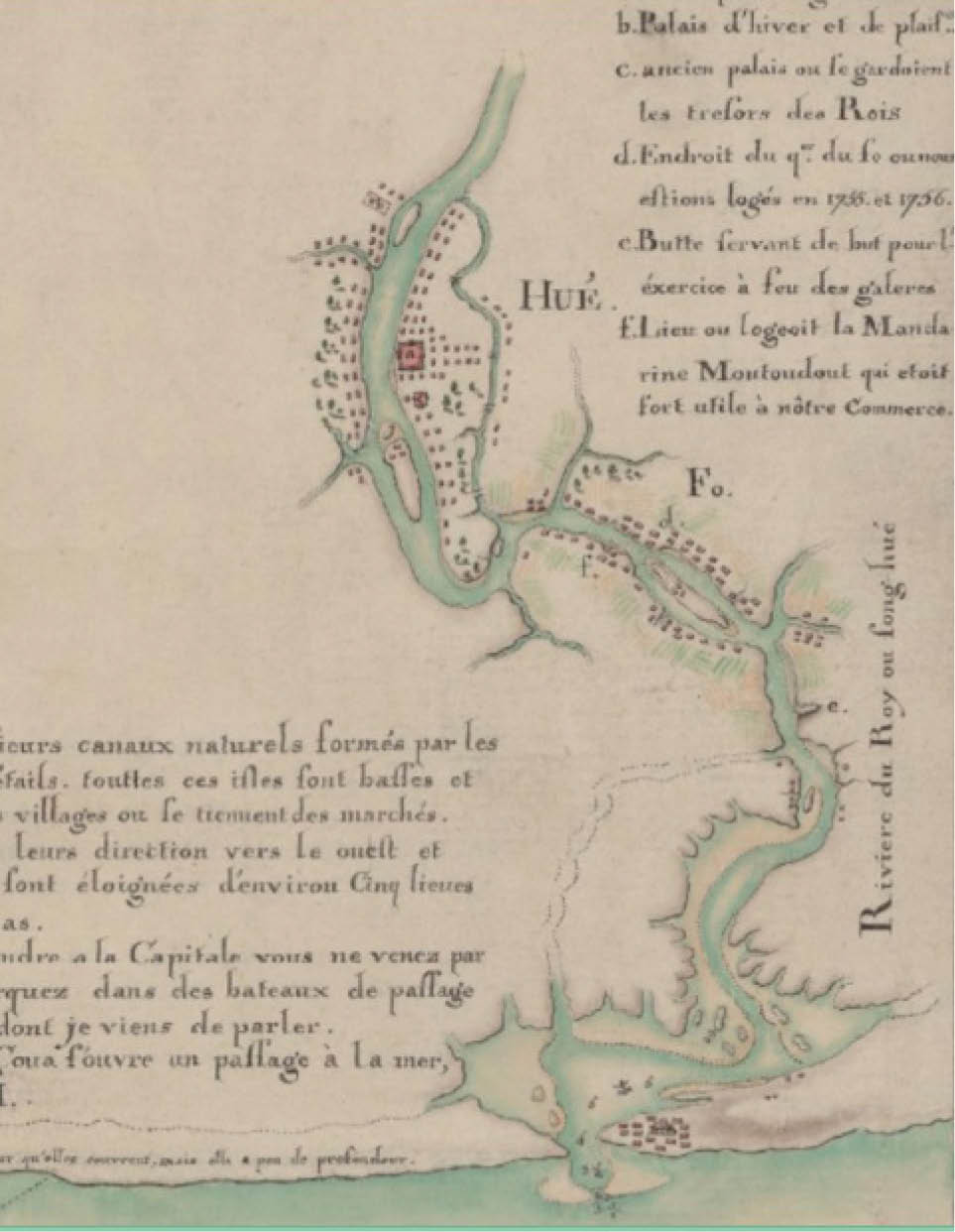

Capital of Phu Xuan (Le Floch de la Carrière, 1755-1756)

Ancestry worship was considered very important throughout the country during Tet. The altar was carefully cleaned, especially the ancestral tablets, representing the ancestry in the eyes of their descendants.

They believed their ancestors' souls came home to visit. They avoided weeping their houses on the three days of Tet because they did not want to hurt their ancestors’ feelings. Death did not mean disappearance, but return, as a saying went: they had left but they would return.

On Tet Holidays, to commemorate their ancestors, people presented lots of offerings. Everyone in the family prostrated in front of the altar to show respect to their ancestry.

During Tet Holidays, people gave parties with a lot of wine. They played cards and many other games. In the imperial city, on three days in a row, the king offered luxurious banquets to mandarins and no one was allowed to refuse. Likewise, the same things happened in all the provinces; the heads of provinces gave parties to their subordinates.

It was the vitality of ancestry worship in Hue that caused the Holy See to adjust the rules for the laity. In 1791 the patriarch of Alexandria_the commissioner of the Holy See in China was sent to Hue to research the rituals. Ancestry worship was eventually allowed because it was not at all superstition, but plain elegance. However, later the Holy See had to withdraw the permission because they felt the risk of serious crises which would decrease the number of Catholics.

At the beginning of the year in Dang Trong, there was the custom of giving gifts to each other. People gave one another poultry, eggs, oranges, cake, etc. Mandarins presented gifts to the king, and the guards, the soldiers to the mandarins; patients to their doctors; laypeople to the missionaries; students to their teachers; children to their parents; and servants to their owners.

Each year, Father Koffler presented to the king and the ministers a bottle of aromatic wine, a bottle of perfume, marinating pills, mung beans, a bottle of medicinal wine for treating gout, paste for headaches and wounds. After 20 days called Dai Nhat (Big Days), offices opened again and all administrative, agricultural and commercial activities came back to normal after the ritual of lowering cay neu.

Arriving in Dang Trong in 1749 -1750, P. Poivre, a French merchant, was very surprised to see the habit of setting up cay neu with a bundle of ribbons of thin cloth or paper bearing characters believed to bring happiness or avoid bad luck on top early in the morning. On Tet holidays people went to pagodas, temples and family worship houses. They also visited friends, drinking wine and eating delicious meals. Absolutely there were no markets on Tet, and people did not kill animals. They just simply had fun. Vo Vuong (Martial Lord) gave the delegation 2 pigs and 20 chickens and ducks as a special gift though he complained about not working on this occasion (Henri Cordier, 1887, "Voyage de Pierre Poivre en Cochinchine”, Revue de l'Extrême-Orient, Vol. 3, Number 1).

Tet Holidays and spring festivities in Hue from Nguyen Lords’ era now have always had many original values. Researching, collecting and reproducing that traditional heritage will make Hue become unique.

Story: Tran Dinh Hang

Photos: Documentary