Whereas the North Vietnam was affected by Chinese culture through conquest and assimilation, most of the Central and South Vietnam have been impacted by Hinduism via trade and cultural exchange for a long time. Owing to its geographical, political and historical position, Vietnam has been under direct influence, creating a durable and tactful honing to find ways to protect and preserve Vietnamese values and identity.

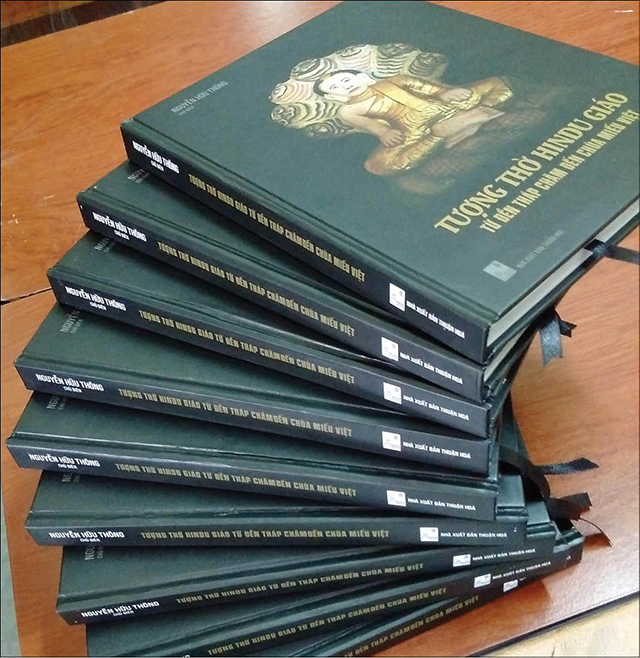

No matter how inactive or proactive in violent fights or peaceful contacts, Vietnamese managed to behave flexibly in their exchange with other civilizations and cultures. On pathway southwards, Vietnamese never repelled or destroyed Champa cultural relics in contact with it. Instead, they conducted and got along with Champa culture, selected qualities and nourished them to create new values in their own cultural treasure without religious and original discrimination. This is the important foundation for cultural characters of Central Vietnam from the perspective of community throughout history. This key issue has been considered, approached and resolved by the sub-institute of Vietnam National Institute of Culture and Arts Studies in Hue via the reference book Hinduist Statues: From Cham Temples to Vietnamese Religious Establishment (Nguyen Huu Thong et al. (eds.), 2017. Hue: Thuan Hoa Publishing House).

It should be highlighted that in Vietnamese southwards march, they proved the proud qualities of generosity and humanity through the challenges of sensitive situations in which they were to decide on a behavior appropriate to Hinduist heritage in Champa. This makes Champa culture an integral part of Vietnam national community properties. As a result of a 10-year community-based research, the reference book has contributed new documents as well as perspectives on Viet – Champa cultural contact and exchange in community life in Central Vietnam through concrete evidence of visual arts, aesthetic values, religion, Viet – Champa cross-culture in the recognition of Hinduist worship statues and reliefs in Vietnamese temples.

The work has thoroughly investigated the worship of Hinduist statues at current religious establishments. Through names and references, worship designs, processing techniques and legends, it specifically examines important matters, namely, the phenomena of cultural transformation and from the view of Central Vietnam (Part 1); The southwards march and the art of conquest from the angle of spiritual culture (part 2); the recognition of Hinduist worship statues in Vietnamese religion (part 3).

The book has been illustrated with vivid data sources obtained during fieldtrips to villages from Quang Binh to Quang Nam, including 222 photos of statues and religious establishments. These deliberately selected and arranged illustrative documents, along with explicit comments and evaluations, have played an important part of the book. The authors’ consistent argument was that the southwards march was not simply the replacement but a process of inter-habitation of Vietnamese and the locals, making a picture of community life in Central Vietnam.

On their arrival at new lands and encountered systems of worship statues of a strange religion, Vietnamese managed to interpret and worship in their own ways. It was the tendency to bring these close to goddess, folklore, official tradition, and Buddhism that effectively Vietnamize the strange and dissimilar Hinduist heritage in Central Vietnam, identifying distinctive values. The Vietnamese southwards march was depicted vividly and creatively with delicate and harmonious interactions and exchanges through various writings and photos.

Through many pages and pictures in the book, the Vietnamese immigration southwards come alive. The process of recognizing, transforming and worshiping the Hinduist statues by the Vietnamese on the new land is closely tied to the aspirations for peaceful settlement under the strange divine powers, and to the sincerity to recognize and attach these mascots to Vietnamese worship and spirit systems.

The effective adjustments in terms of shape, design and name have brought the Shiva, Vishnu, Brahma, Uma, and Po Nagar into Vietnamese spiritual world as the reincarnation of Avalokitesvara, Bodhisattva, Mrs. Duong, and Mrs. Yang, or as “Vietnamese gods from Champa origin” (Mrs. Loi, Mrs. Thu Bon, Thai Duong Phu Nhan (‘Sea God’s Wife’), Bo Y Na or Thien Y A Na). As a result, Hinduist statues became divine statues worshiped and preserved in a natural, voluntary manner from pure Vietnamese view, and remained unchanged in spiritual life up to now.

By Minh Phuong